|

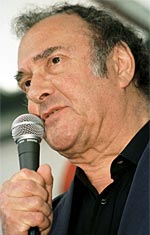

Harold Pinter by Mark Brown Harold Pinter, who died on Christmas Eve, aged 78, was, arguably, the greatest English playwright of the 20th -century. From early dramas, such as The Birthday Party (1958) and The Caretaker (1960), through such remarkable works as The Homecoming (1965) and No Man’s Land (1975), to the powerful One for the Road (1984), his theatre was startlingly original, breathtakingly poetic, disconcertingly ambiguous and profoundly humane. In many ways the successor to his friend and mentor Samuel Beckett, Pinter constructed plays which were often deceptive in their domesticity. Just as Beckett’s abstract locations enabled him to speak to something seminal and universal in human experience, so Pinter’s rooms were places in which conversations became carefully observed power games and physical movements and gestures were of extraordinary import.

Pinter wrote (in 1958) that, in the theatre, “a thing is not necessarily either true or false; it can be both true and false.” His explorations of that idea through his characters continue to offer us remarkably deep and complex insights into our own lives. Pinter’s early career as a stage actor gave him a profound understanding of the theatre. However, his writing talents extended beyond the stage. His screenplays, such as The Servant (1963) and The French Lieutenant's Woman (1980), earned him critical acclaim. His voice was expressed in poetry, too, where his succinct wit was often employed to powerful political effect. Pinter’s artistic genius was inseparable from his fierce sense of political justice. In 1948, during conscription, he refused to don the “shit suit”(as he called the British Army uniform); as Michael Billington recounts in his fine biography of Pinter, only a combination of an unusually lenient magistrate and the willingness of his father to pay his court fines kept the young Pinter out of prison. An active anti-fascist since his youth, Pinter, who was Jewish, famously laid out a racist loudmouth who was spouting anti-Semitism in a London bar in the 1950s. This political awareness and commitment would lead to Pinter becoming one of the most robust and scintillating spokespeople on the British left. This was particularly clear in his brilliantly expressed abhorrence of the imperialist wars in Iraq and Afghanistan and Israeli oppression of the Palestinians (Pinter was a founder member of Independent Jewish Voices, an organisation which challenges the assumption by Israel and its supporters that they speak for all Jews).

It was much to the chagrin of New Labour, and the entire British establishment, that Pinter received the Nobel Prize for Literature in 2005. His acceptance speech – which he had to record in London, due to ill-health – is a superb piece of prose, offering wonderful artistic insights and, in greatest measure, devastating and incisive political commentary. As so often, the chief target of his penetrating intelligence and dark satire was US imperialism, which, Pinter repeatedly reminded the world, was responsible for the greatest mass murder seen since the Nazi Holocaust. It was my privilege and honour to know Harold Pinter. We met when he agreed to be interviewed by me for a newspaper article following the attacks in the US on September 11, 2001; an interview in which he warned against the impending disaster of the US/British invasion of Afghanistan. The signed copy of his plays Celebration and The Room which he gave me on that occasion remains my prized possession. Pinter and I were in touch on a number of occasions after that. On each occasion, he exhibited the combination of generosity, intelligence and love for language that characterised both his art and his politics. When his friend, the great American playwright, Arthur Miller died,

Pinter said of him: “[H]e was a highly dignified and an extraordinarily

formidable man, an independent man… He was so honest and a man

of rare integrity in his writing.” Words which apply equally to

Harold Pinter himself.

Mark Brown, first printed in Socialist Worker

|