|

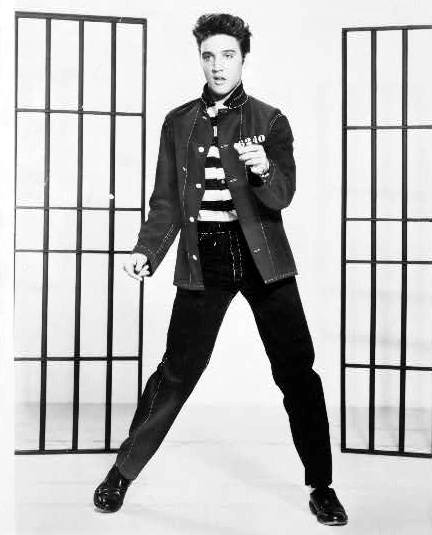

Elvis was a hero to most Elvis Presley:

The king of rock’n’roll, died 30 years ago this month. Ian Birchall looks at the contradictions and the tragedy of his life When Elvis Presley died, 30 years ago this month, punk was at its peak. At some punk gigs there was cheering when the news was announced. Elvis was everything the punks despised – old (over 40!), rich and best known for tedious ballads like “The Wonder of You”. Yet without Elvis, neither punk nor most of the popular music of the last 50 years would have been possible. A whole generation took Elvis as their starting point.

Bob Dylan first got into rock music through hearing “Hound Dog”. Otis Redding started out singing Elvis songs in local talent shows. John Lennon said, “Before Elvis there was nothing.” Jimmy Page was inspired to learn the guitar by Elvis’s “Baby Let’s Play House” . His first British hit, “Heartbreak Hotel”, sums up what was so startlingly new about Elvis’s music. The song was a tale of bleak despair, based on a newspaper report of a suicide note. It was a thousand miles from the sugary love songs that had dominated the charts. Elvis came to prominence as musical segregation was breaking down. White musicians began to play black music, and black musicians like Chuck Berry and Little Richard got a white audience. The fusion of black and white music that Elvis created was at the very heart of this process. It is often said that Elvis stole black music. There is much truth in this. His first hit was a cover of “That’s All Right” by Arthur Crudup. Crudup never got his royalties and died in poverty.

The full story is more complicated. Jerry Leiber, one of the writers and producers of “Hound Dog”, was the son of Jewish refugees from Poland. His mother kept a grocery store in Baltimore, and was one of the few local shopkeepers who gave credit to black customers. As a delivery boy Jerry was often in black homes and was captivated by black music. In 1953 “Hound Dog” was a hit for Big Mama Thornton, but only on radio stations specifically aimed at a black audience (see » www.youtube.com/watch?v=P3s4v-02P6c). In 1956 Elvis rerecorded it and won a new audience for the song – and the style – which Thornton could never have dreamt of. Segregated As a result Elvis made many enemies. When he performed on the Grand Ole Opry, a well known country and western radio show, he was told “We don’t do that nigger music around here – go back to driving a truck.” Southern US clergymen denounced him for playing “jungle music” . In Britain there was widespread racism, but music was not as segregated as it was in the US. The first black musician to top the charts was pianist Winifred Atwell in 1954. Elvis was adopted by a new generation of British youth that had grown up after the Second World War, knowing nothing of the mass unemployment and defeats of the pre-war period. As a result it was far more assertive. Elvis’s sullen aggression responded to a new mood. As he sang in “Trouble”, “I don’t take no orders/From no kind of man”. Elvis summed up a mood of anti-authoritarianism. His films encouraged an active response, notably jiving in the aisles. Rock’n’roll and Elvis in particular were blamed for juvenile crime, then – as always – said to be increasing. In fact, research published in the New Society magazine showed that the music channelled aggression and reduced violent crime.

Elvis challenged the dominant ideology which made up the fabric of society – racism, sexual conservatism and respect for authority. But he was also a source of massive profits. In the post-war economic boom, young people no longer moved overnight from childhood to adulthood. Teenagers were invented. In 1956 the US’s 13 million teenagers had an annual income of $7 billion. Dollars to be spent on records and clothes. “Blue Suede Shoes” celebrated a generation for whom clothes were more than a means of keeping warm. The young man who defended his blue suede shoes against all comers would be less willing to accept the traditional discipline of school and factory. Unfortunately the left was looking the other way. The New Left that had emerged after the Suez crisis defeat for British imperialism and the revolt against Stalinism in Hungary in 1956 preferred jazz and folk music. Illuminated Communist intellectual Eric Hobsbawm declared that “the habitual rock-and-roll fan, unless mentally rather retarded, tended to be between ten and 15 years of age.” Elvis’s career illuminated a contradiction at the heart of capitalism. Capitalism needs to generate profits in order to survive. But to suck profit out of workers it also needs an ideology to ensure that workers know their place in society. Money won. The shareholders of the record company were more powerful than smalltown clergymen who wanted Elvis banned. There was always an element of fraud in the promotion of Elvis. His second film, Loving You, was quite cynical about how scandal can be manipulated to promote a reputation. Sometimes it seems to anticipate the film about the Sex Pistols, The Great Rock’n’Roll Swindle. Elvis’s sexually provocative gyrations were enhanced by hanging the cardboard tube from a toilet roll on a piece of string inside his trousers.

Elvis’s early films were simply vehicles for his songs. In 1960 he made a different kind of movie. In Flaming Star he played a young man of mixed race – white and Native American – caught up in the conflict between two communities. It was a powerful statement against racism, and while it was banned in apartheid South Africa, the Los Angeles Native American community inducted Elvis into its tribal council. It was Elvis’s best acting performance. But it didn’t make money. After that Elvis appeared in a series of banal films in which the location constantly changed (Blue Hawaii, Viva Las Vegas, Fun in Acapulco), but the plot remained mind-numbingly the same. Musically he retained – at least partially – his magnificent voice, but was given increasingly mediocre material. His manager, “Colonel” Parker, refused to let him meet songwriters and kept complete musical and financial control in his own hands. Elvis was given tedious ballads and second-rate jingles. Listen to “Baby Let’s Play House” (» www.youtube.com/watch?v=QI97stLQLdw) followed by “The Wonder of You” to see how a great singer can be degraded. Elvis’s early music had drawn on the power of black music. In 1969, when it was felt that a “socially aware” song would be profitable, he was given the appalling “In The Ghetto”, which depicted blacks as helpless victims. Powerless Elvis was rich but powerless. He once flew his private four engine airliner nearly a thousand miles – to buy peanut butter sandwiches. He could still pull the crowds – the pampered rich in Las Vegas – but a new generation of musicians were making innovations he could not follow. Unlike Elvis they wrote their own songs and at least tried to control their finances. Elvis controlled nothing. He despised the music and films he was forced to produce, but the “Colonel” had the last word. He turned to pornography, mysticism, and increasingly drugs. His doctor prescribed whatever he wanted. At 42 he was dead, killed by the system which for a brief moment he had seemed to challenge. One of the first people to see his corpse was the great black singer James Brown, who had known him many years. He murmured, “Elvis, how you let this happen?” Elvis posed a dilemma for capitalism, but it was not an insurmountable one. Eventually it preserved him as a commodity but destroyed him as a musician. Often this is blamed on “Colonel” Parker. Parker was both incompetent and scared that Elvis might do something outrageous or unpatriotic. But things would have gone the same way without Parker. As Karl Marx noted, “capitalist production is hostile to art and poetry”. Music cannot change the world, but it can inspire those who have the potential to change it. Elvis was no socialist, just a rebel against a system he never understood – and his rebellion produced some of the great music of his century.

Ian Birchall in Socialist

Worker |