|

Not taken at face value Shakespeare’s The Merchant of Venice is about

the battle between ways of making money, not between Jew and gentile,

says Mike Rosen

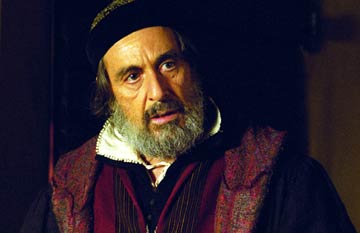

For many, the play is too uncomfortable, particularly since 1945, when the world saw what a modern European state machine had done to the Jews. As people have grappled with how this could have happened, the name of Shylock has often cropped up. Along with thousands of other representations of Jews as vengeful, money-crazed, blood-sucking devils, Shakespeare has been accused of creating a frame of mind that helped the Nazis’ genocide. In case you don’t know the play, the deal is this: middle class Bassanio wants to get off with Portia, an upper class lady. For this, he needs wealth, but he has spent what he’s had, some of which he borrowed from his friend, the merchant, Antonio.

Antonio is a trader with ships ferrying all over the known world. He hasn’t got the readies, so he goes to Shylock to borrow. A deal is struck, whereby Shylock waives the usual rate of interest but says that if Antonio can’t deliver on pay-back day, Shylock must have a pound of his flesh. Meanwhile suitors are turning up to woo Portia, who has set them each a puzzle: they have to choose which of three caskets, gold, silver or lead to open. He who chooses right wins her. Shylock’s daughter, Jessica makes off with one of Bassanio’s pals (non-Jewish) and Antonio’s ships are reported as having sunk. Shylock wants revenge for the loss of his daughter and says he’ll have his pound of flesh off Antonio. Up at Portia’s place, Bassanio chooses the right casket—the lead one. In court, Shylock won’t let Antonio’s friends pay the debt. He wants the flesh. Portia, dressed up as a lawyer, pleads with Shylock to show mercy. When he doesn’t, she says, go ahead, cut Antonio open but remember it must be exactly one pound and the deal doesn’t mention blood. So do the deed without shedding blood. Shylock realises that he can’t. He makes to leave, but Portia says that as an “alien” who has threatened someone’s life, he must give up his loan—let Antonio “use” half his wealth, the other half goes to the state and it’s up to the ruler of Venice to decide if he can live. The Duke pardons his life, Antonio asks the Duke to give up his half on condition that Shylock converts to Christianity. Antonio gives his half to the man who got off with Shylock’s daughter. Shylock must agree to write a will, leaving everything he has to his estranged daughter and husband. Then, Bassanio marries Portia (as do each of their servants), even though Bassanio fails a test of loyalty concerning a ring. It turns out that Antonio’s ships didn’t sink but are “richly come to harbour”. Shakespeare has Shylock powerfully defend his right to be not persecuted and at the end we have a strong sense that he is humiliatingly impoverished and de-cultured. If we typify the play as a morality tale about the treatment of Jews, it misses the real struggle going on—a battle between two ways of making money. Antonio is a member of the new rising class, the mercantile capitalists. He buys to sell. Shylock makes money out of “dead” capital, lending and getting back more. At this stage in history, the merchant class, desperate for money to finance their adventures, struggled with the monopoly of the moneylenders and overcame it. They abolished the Christian (not Jewish) taboo against taking interest on loans and set up their own credit houses. Shakespeare shows us part of this very struggle and asks us to consider the values (it’s a word that crops up in the play many times) of the new class. He shows their waste, their deceits, their cruelty, even as they talk of mercy, and how even as they talk love, they talk money, taking care to marry into the aristocracy to assure their place in the ruling class. He asks us, are they any better than those beastly Jews? It’s a question that assumes an anti-semitic standpoint. But in asking it, Shakespeare lets us see the values of the class rising to dominance wanting to be free of the constraints of a money market they couldn’t control. At this point in history, they didn’t have Gordon Brown to help them. From Socialist Worker

|