|

'This album could seriously damage us' Manic Street Preachers ... revisiting their heart of

darkness. Alexis Petridis, The Guardian, Friday 8 May 2009 As Nicky Wire is keen to point out, the Manic Street Preachers' new album was James Dean Bradfield's idea. "Yeah," nods Bradfield. "I'm thinking, why are you so eager to say that? Is it because he knows this hasn't got such a commercial aspect to it? Is he waiting to go, 'Yeah, we did good with Send Away the Tigers and you had to go and fuck it up with this idea?'" He laughs, a kind of warm but vaguely exasperated, what-can-I-do? laugh that you suspect has seen a great deal of service over the 21 years he's spent in a band with Wire, a man he describes as "the best friend I've ever had", but who nevertheless has a habit of "dropping bombs everywhere" - of suddenly announcing the band was going to split up after one album or that he hoped other rock stars died, viciously attacking other artists in interviews, and apparently going out of his way to make people hate the Manic Street Preachers. This time, however, it was Bradfield's turn to drop a bomb. "I was actually really shocked," says Wire, "because it's usually the kind of dumb-ass thing I say after we've had success. You know, after This Is Your Truth sold 4m copies: let's not get any bigger, let's go and do a gig for Fidel Castro, annoy everyone in the world. Let's spend 300 grand doing a gig for a communist system we don't really believe in."

Listen to Nicky Wire talking to Tim Jonze about the disappearance of

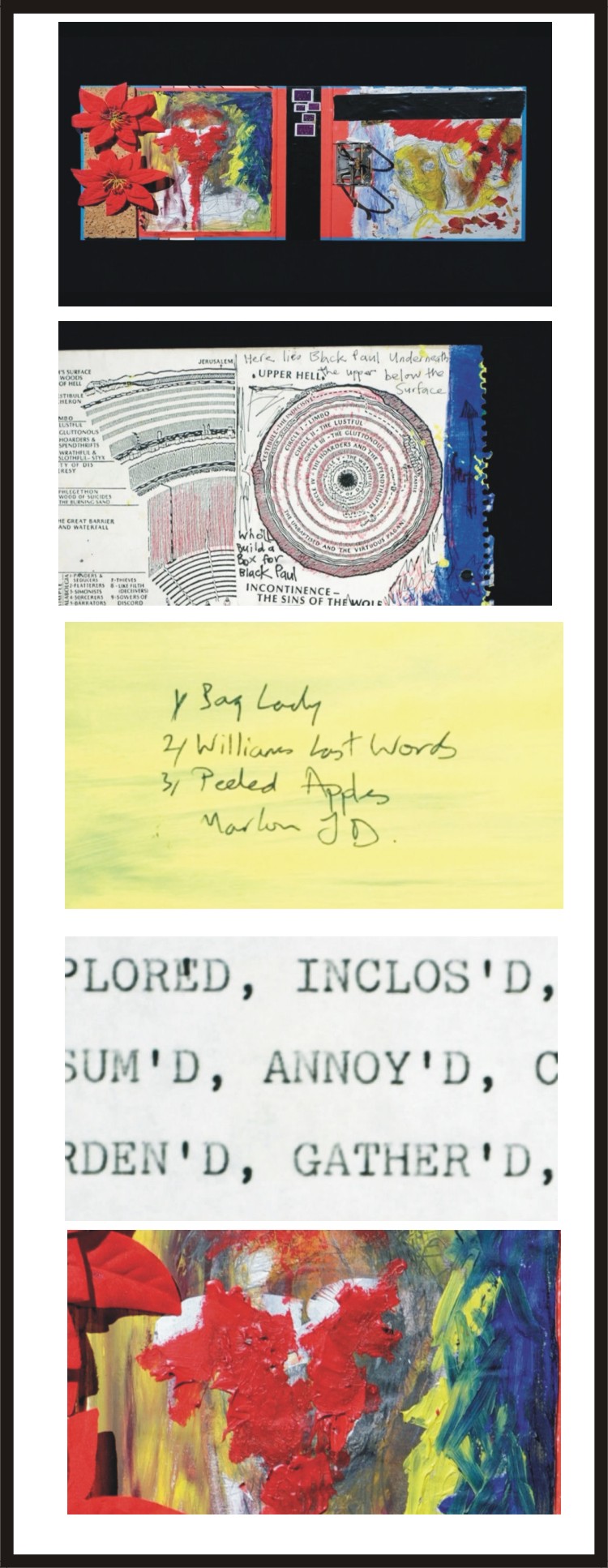

Richey Edwards Link to this audio "We were saying, 'Fucking hell, it's going to be hard following up a No 2 album, but we've got to start,'" Bradfield says. "A week before I'd been looking at Richey's lyrics anyway. Two or three times a year, I'd get them out and look at them, and every time it was always the same reaction: I'd always imagine putting music to them, then I'd get a bit scared and put them back in a drawer. But this time I'd looked at them and it was the first time I couldn't stop turning the pages and I was getting ideas and stuff. Quoting the film The Contender, it was an idea whose time had come. I said, 'By the way, I really want to try and do the Richey lyrics.'" The lyrics were in a folder that Manics guitarist Richey Edwards had given to Wire in early 1995, with a picture of Bugs Bunny and the word "opulence" scrawled on the front and the words to 30 or so potential songs inside. The bassist didn't invest any great significance in the folder at the time - the band had tentatively started work on a new album and Edwards "was so prolific at the time, he couldn't switch off" - nor in the other gifts that Edwards had given his fellow band members. "They were nothing big, just little bundles. He gave me a Daily Telegraph and a Mars bar, two things I liked - the sports section of the Telegraph is still the best. I just saw it as an act of kindness for the fact that he'd been pretty difficult."

In any case, Edwards appeared to be on the mend, after a horrific 1994 during which his drinking and self-harming had spiralled out of control. There had been a disastrous tour of Thailand, where Edwards slashed his chest onstage with a knife given to him by a fan while a horrified NME journalist looked on. Back in Britain, he cut himself so badly he ended up first on an NHS psychiatric ward, then in a private clinic where he was treated for alcoholism. The band trudged grimly on without him, promoting their new album, The Holy Bible, packed with lyrics written by Edwards that cast at least some light on his increasingly desperate mental state: "Can't shout, can't scream, hurt myself to get pain out," ran one line in the single Yes. He rejoined in time for a Christmas gig at the Astoria in London, which concluded with the band smashing up not just their equipment, but the venue's lighting as well: they caused £26,000 of damage. "From Thailand to the smashing up of the Astoria, it was hospitalisation, no money, drudgery, hateful, miserable, awful," says Wire. "It felt like Richey was drifting away. I'd just lost him. Couldn't talk about rugby or cricket or football. He'd call you up at strange times about some documentary he'd just seen or something he'd tracked down. It was hard work, it was baffling at times. He was finding it really hard to sleep. When people talk about the wounds or the blood, the only real tragedy is when you lose someone kinetically, someone you've known since he was five, you've done all those things with and you feel you can't communicate. It was terrible. But in the last three weeks, there was a serene calmness to Richey, he was laughing more, the pathos and the irony were back. Maybe that's because he had reached some conclusions and he just felt some inner peace. We did a recording session and came up with some great tracks. So the Daily Telegraph and the Mars bar, I just saw it as a little 'Things are going to be OK'. Which maybe, in his mind, that's what it was." He sighs. "But different meanings of OK, I guess." On 1 February 1995, Edwards disappeared, checking out of his London hotel on the day he and Bradfield were due to fly to the US on a promotional tour. His car was discovered abandoned two weeks later at the Severn View Service Station. His body has never been found, but he was officially presumed dead at the end of last year. The band carried on to vast commercial success, using a handful of Edwards's lyrics on 1996's breakthrough album Everything Must Go. Wire remembers playing their Millenium Eve gig in Cardiff - the biggest indoor music event in the world that night, according to the BBC - and hearing 62,000 people singing Edwards's words on Small Black Flowers That Grow in the Sky: "It was just bouncing back off the stadium wall - 'harvest your ovaries, dead mothers crawl'. You can see me onstage, thinking, 'Fuck, that is subversion, he must be having a smile somewhere about that.'" Nevertheless, the lyrics in the folder remained untouched. Bradfield had shied away from setting them to music, not least because the folder also contained Edwards's idea for how he wanted the Manics to progress musically - "Pantera meets Screamadelica and Lynton Kwesi Johnson" - and the band had conspicuously, if understandably, failed to transform themselves into a heavy metal/indie dance/dub poetry hybrid in the years since his disappearance.

Wire too had been "scared to look at them". "Not out of some doomsday scenario, it just felt ... I just needed ..." His voice trails off. "The one thing I think we've just managed to do for all our ups and downs since Richey disappeared is never appear to be trying to be like we were when he was in the band. We might have fucked up, but we never did that." When he did take a look, he says he was simultaneously astonished and baffled. Despite being written in the pre-internet era, some of them appeared to be about very noughties topics: the numbing effect of information overload, the corrosiveness of celebrity culture. Others were screeds of impenetrable, densely packed imagery that, as Wire points out, don't much resemble anything else in rock. The visceral hatred and despair of The Holy Bible is noticeable by its absence, although it's difficult to overlook the similarity between the lyrics of William's Last Words, which Wire edited down from a long prose piece, and a suicide note: "Wish me some luck as you wave goodbye to me, you're the best friends I ever had." Wire insists he thinks the lyric isn't about Edwards, but nevertheless, the process of editing it down was "pretty choking". Today, talking about the lyrics and the resulting Steve Albini-produced album, Journal for Plague Lovers, in the plush bar of a West End hotel, there's a minor but noticeable difference between Bradfield and Wire. Both are justifiably proud of the album, which bullishly invites comparison with The Holy Bible: same number of tracks, same typography, another painting by Jenny Saville on the sleeve. But Wire, while open and friendly and charming, seems slightly more uneasy about the album than his bandmate. As he talks, he keeps putting on and taking off a pair of sunglasses. Bradfield thinks he's worked out what at least some of Edwards's more obtuse lyrics are about, Wire has "tried not to interpret". He spent time after Edwards's disappearance "looking for clues" in the folder; Bradfield did not. "As soon as I realised everyone was trying to do a Columbo on Richey, I stopped looking in bags for notes, I stopped looking for messages in lyrics because I knew they weren't there. He wouldn't be that crass," Bradfield says. At one juncture, after listening to the finished album in the studio, Wire suggested they didn't release it at all. "I said, 'Let's just fucking dig a hole and bury it and make it even more of an art statement, say we've made this great album, but it's just too much to give away.' James was like: 'After I've done all that work? Fuck off!'" There's a chance Wire's unease has something to do with the album's uncertain commercial prospects. Even by their standards, there's a certain wilful contrariness in working so hard to re-establish yourself in the musical mainstream as the Manics did with Send Away the Tigers, only to follow it up with an album that invites comparison to your most notoriously uncommercial work, filled with songs called Jackie Collins Existential Question Time and She Bathed Herself in a Bath of Bleach, and lyrics not even the performers understand, that furthermore comes dressed in a sleeve featuring a painting of a child's blood-spattered face. "This album could seriously damage us in a commercial sense," he says with a nod. "Already, supermarkets won't accept the album cover, which I am really startled at. You can have the Pussycat Dolls poledancing, but you can't ... " His voice trails off again. "So already I'm thinking, 'Oh fucking hell, are we putting them off already?'"

Then again, as Bradfield points out, wilful contrariness has always rather been the Manic Street Preachers' thing. "We came from the Valleys, we were Valley Troglodytes and proud of it, but we were ferociously nerdy indie kids as well. But we were ferociously nerdy indie kids who loved sport, which other ferociously nerdy indie kids didn't. When we first came to London, we were always trying to work out a way of making people try and believe in us while making people hate us at the same time." In any case, he says, this was an album they almost had to make, regardless of the reaction. "Deep down I was thinking, I couldn't have changed that much, I couldn't have forgotten that much about Richey that I can't do this. If we couldn't reconnect with what Richey wrote, even at the apex of what was happening with him ... fucking hell, if we couldn't do that then we would have lost a part of ourselves that we hadn't even realised we had lost." • Journal for Plague Lovers is released on 18 May on Sony

|

.jpg)